(2024/01/31 update: slightly edited post-publication.)

Friends - very nice to hear from some of you after my last post, on travel to Awaji and the start of the spring semester.

As I wrote last time, this is my 10th year of teaching what’s now Strategy for the Networked Economy. Over time I’ve changed the course from a vertically-oriented course (Corporate Strategy in Telecom and Media) to one centered around network effects and platforms. Below are readings up on the background wall during class last week.

There are a few case companies that have remained a consistent part of the class, such as Nokia; Bharti Airtel; and Netflix. How we discuss - and most importantly, how and what we extrapolate - from those cases has changed. Generally, I think of strategy cases as a pairing - if, say, Nokia is the case company, what’s the right article or concept from strategy to pair with it? Or, vice-versa, if the goal is to introduce, say, the Value Net from Nalebuff and Brandenburger, then what are the right cases or examples to pair with it?

In this post, I’ll focus on lessons from Nokia, specifically the fall of its handset business (happily, its infrastructure business is still going) and some very germane lessons from that.

Why I love starting with this case - there was a time when Nokia was synonymous with phone! Success today does not ensure success tomorrow.

(Btw, Jan Chipchase, whose work I’ve borrowed here, had what I imagine would have been one of the coolest gigs on earth - ethnographic researcher for Nokia. I had the pleasure of hearing him speak after he’d moved on to Frog Design.)

Below is Nokia segment revenue (source: Capital IQ) from 2019-2023. 2019 is chosen as starting point as that’s when the transition to 5G in certain countries began in earnest.

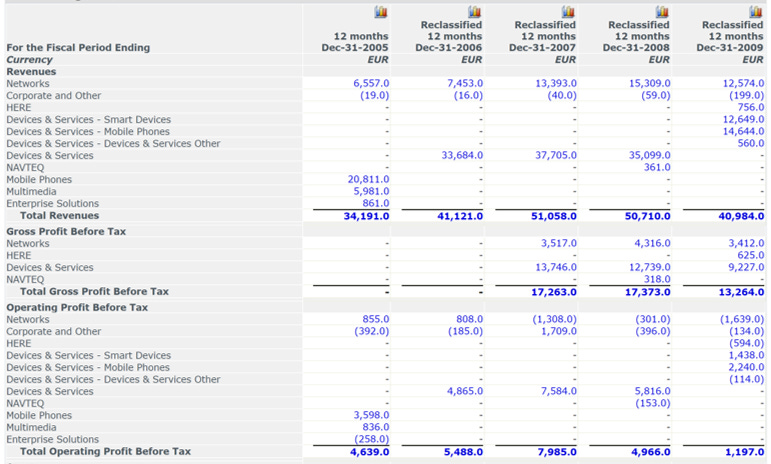

Not shown here, of course, is Nokia’s former handset business. For that, we’ll look back further, to 2005-2009, shown below.

2007 is, of course, the year the first iPhone launched; 2008, when Android launched.

So on a revenue basis, Nokia is about 40% of its former peak. In infrastructure, it is one of the global big 3, along with Huawei and Ericsson, or as Dell’Oro puts it below, one of the global Top 7.

The case we use in class focuses on the rise and fall of Nokia’s handset business. One extrapolatable insight from that: the opportunities and risks in the handset upgrade cycle.

This picks up on Clayton Christensen’s description of hard disk drive companies as the “fruit flies” of tech, due to what was then rapid iteration in storage technologies.

For smartphones, New Every Two (years) has become New Every Three (or more), depending on the country and customer. This has an impact on the rate at which new innovation propagates out to consumers, but the broader point remains - if, a market has, say, 400M active smartphone lines, then each year one-third or 133M of those will upgrade.

In 2014, I had a project with the R&D office of an international Android handset maker. A rule of thumb cited by the client was that the US smartphone market had a 40:40:20 composition: 40% loyal iOS customers; 40% loyal Android; and 20% who were Switchers who would listen to the best offer available at the moment.

At a once-every-three years upgrade cycle in a market with 400M subscribers, that implied that each year, around 27M customers were in play as potential OS-agnostic Switchers, and, among Android loyalists, another 53M were in play. So each year, maybe 80M subscribers were up for grabs (if not netting out the client’s own customers). They could be retained or enticed away from another handset maker.

(Btw, today the US market is around 55% iOS, 45% Android, whereas global share is more 30:70, iOS : Android. N.B.: among my students, iOS share is usually around 85-90%.)

Here, what we call channel advantage in class matters - if, say, Samsung can flood the carrier or retail channel (as it does), then it is possible to deny competitors oxygen, i.e., shelf space and exposure. So how and where consumers buy their phones matters. Here, I think back on HTC’s last marketing hurrah in the US market - its HTC One ads with Gary Oldman.

I was an HTC loyalist, but the phone itself was hard to find at retail. And I wanted to find it.

So, can companies keep their customers as they upgrade? And can they make sure they are among the choices being presented by channel partners, if devices are being sold bundled with service by a service provider partner, as is usually the case with postpaid wireless service?

At the recommendation of Nitin Shah, formerly with Nokia (and Bell Labs, pre-Nokia), in 2019, I read Transforming Nokia: The Power of Paranoid Optimism to Lead Through Colossal Change, former Nokia chair Risto Siilasmaa’s account of his years on the board and in the chair role. This came out in 2018, seven years after Stephen Elop’s burning platform memo, and seven years after the decision to adopt Windows Phone.

Siilasmaa’s book is riveting, and refreshingly honest. He adds perspective on internal circumstances and cultural barriers as Nokia was assessing how to respond to smartphones. This is a Build, Buy or Partner decision. Siilasmaa’s account makes clear that Build (improve Symbian, or roll out Meego) really wasn’t a viable choice. He also attributes a comment to Steve Jobs that Jobs had apparently made to Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo (aka OPK), then CEO of Nokia - that Jobs didn’t see Nokia as a competitor, since Nokia wasn’t a platform company. Microsoft, however, was, in Jobs’ view.

Nalebuff and Brandenburger released Coopetition in 1996. They introduce the concepts of complementors and the Value Net. (Some call this the Sixth Force to Porter’s Five.) Usually, introducing complementors leads to some discussion with students about the difference between a supplier and a complementor. N&B answer this as described below:

The Intel Inside campaign is, of course, a classic example of this.

I use a different Intel example in explaining the benefit of lining up providers of complementary products - Intel’s Centrino campaign, in 2003. In rolling out chipsets with Wi-Fi capability, Intel and T-Mobile made sure to line up Starbucks, airports, makers of Wi-Fi dongles. Beyond that, the campaign drove the shift to portable computing, from desktops. The campaign itself became shorthand - Centrino moment — for breakout moments for new technologies. (Intel itself used it recently in talking about Meteor Lake.)

(In dealing with Intel’s investment team in the late 2000s, I will comment that team may have learned some unfortunate lessons from Centrino’s success - Intel was well aware of its own enabling power, and felt it hadn’t sufficiently captured downstream value from services it had helped enable with Centrino.)

Android had its Centrino moment in the US with Verizon’s Droid Does campaign, in 2009.

They are a bit of a contrast with the Lady Gaga ads KDDI used in Japan to promote Android AU.

This gets us back to our Nokia case.

Nokia has adopted Windows Phone. What next needs to happen? Here, a stakeholder exercise helps identify key stakeholders, and, importantly, stakeholders that can help catalyze other stakeholders. We need to line up developers, and network operators.

Of course, in real life, this didn’t happen. I recall visiting a Verizon store on Pine Street in San Francisco and the Windows Phone display being basically a pop-up table. This was not a serious, nay, borderline unavoidable promotion. MUNI stops did not have Windows Phone ads. Nor did developers flock to it. The absence of complementor commitment meant no Centrino moment and Windows Phone petered out.

This gets to a measure of what makes a Centrino moment: the moment when third-party complementors are visibly putting their own resources behind adoption of the new innovation, through campaigns, development resources, shelf space, etc.

The inability of companies with the resources of Nokia and Microsoft to solve the Cold Start Problem is where we pick up the following week, naturally, with Andrew Chen’s The Cold Start Problem, and Cusumano, Gawer, and Yoffie’s The Business of Platforms.

But, there’s another potential takeaway to the case, in that it presents a potential false dichotomy of choices: Windows Phone or Android, not Windows Phone *and* Android. Hence the sub-title in the post: What Would Samsung Do?

Samsung’s ability to throw resources at opportunities (or problems that need fixing) is well-documented, ironically, even in a book about the success of the iPhone (Brian Merchant’s The One Device). Not all of those initiatives would succeed, and, of course, I am assuming sufficient resources to launch both Windows Phone (which Nokia did, unsuccessfully) and Android (which Nokia did not, likely leaving surer revenue on the table).

I still do wonder what would have happened if Microsoft had focused either gaming (pairing with its Xbox business), or on the IT services channel, i.e., selling Windows Phone to enterprise and government clients through the channel….

With that, I’ll wrap up with a Miles Davis track from 1958, from the Elevator to the Gallows (Ascenseur Pour L’echafaud) soundtrack. A search for “Miles Davis” and “cool jazz” usually turns up articles on The Birth of the Cool. This track came after Birth of the Cool and before Kind of Blue. It was allegedly recorded in a spontaneous nighttime jam session in France, because, of course it was! I was writing this post at night, and well, this track was the perfect accompaniment.

Onward and upward,

Jon