If you build it, will they come? (Part 1)

Three points on the significance of *where* semiconductor fabrication happens

(N.B.: corrected a calculation post-launch)

Friends - A warm welcome to summer! And a hello and thank you! to new subscribers/followers. In this newsletter I generally cover themes related to my instruction:

Strategy for the Networked Economy

Clusters: Locations, Ecosystems and Opportunity

Business in Japan

Opportunity Recognition in Silicon Valley

Thanks for being here! Looking forward to your feedback.

Last post, I celebrated commencement week at UC-Berkeley and previewed a talk on in Tokyo on May 28 on semiconductor clusters.

This will be the first part in a two-part sequence on what I covered in my talk on 5/28 on semiconductor clusters. I made three points (listed below) about the significance of *where* semiconductor fabrication happens. I will put Point #3 - economic security, in its own post, as the concept itself merits clear definition.

Subsequent (or in between) those, I’ll cover a trip to Tottori, Japan’s smallest prefecture by population (and last to get a Starbucks, as locals and Tokyoites alike will bring up), at the invitation of the Tottori Industrial Promotion Organization.

After that, I’m planning to get into findings from interviews and research on Open RAN. (Open RAN may be the headline, but the real story there is - both network operators and governments have stake in developing a more diverse supplier base.)

On to our post.

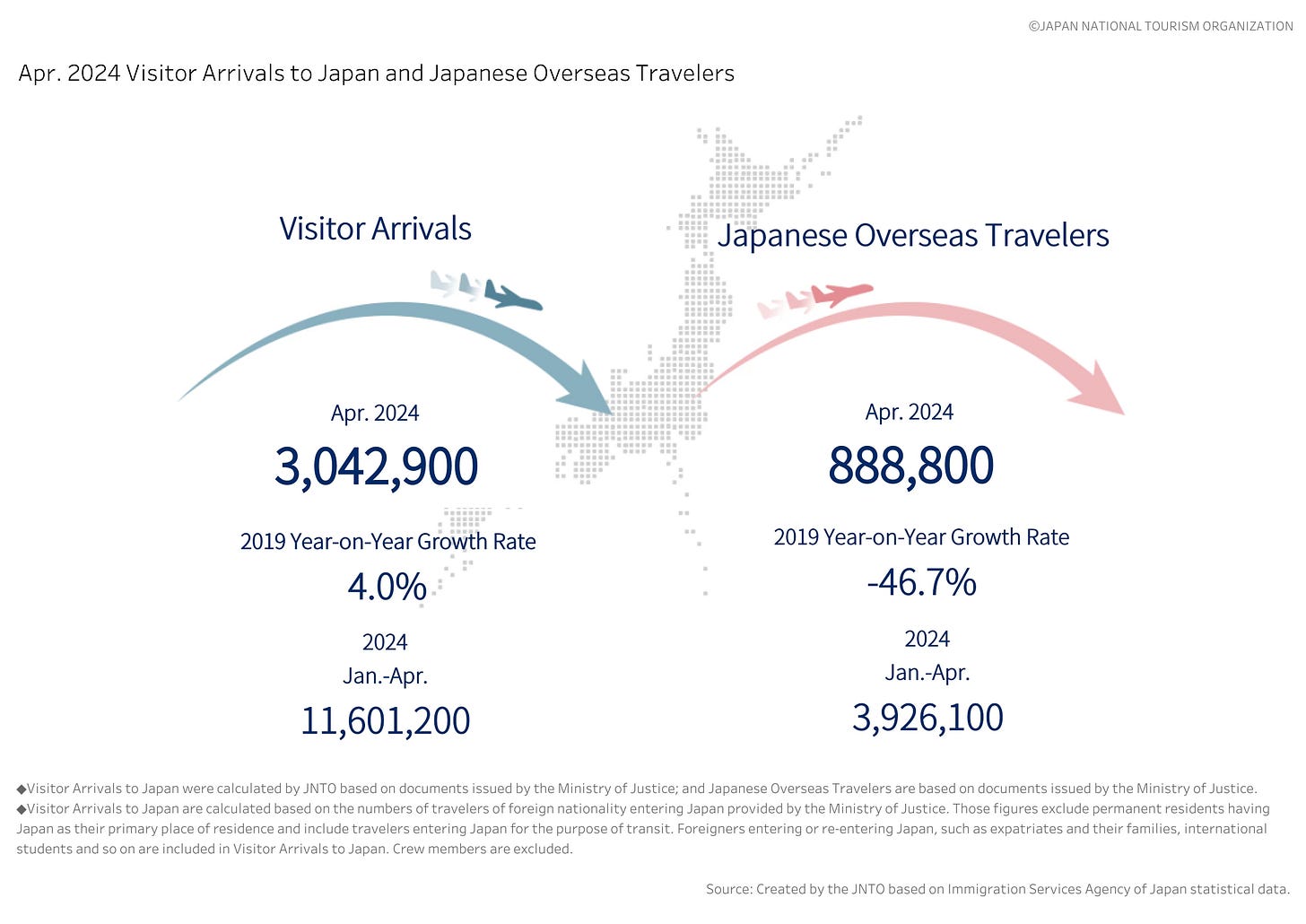

Being in Japan in late May was a chance to confirm all the headlines about the influx of tourism. Below, data from JNTO comparing inbound travel into Japan, and outbound (international) travel by Japanese. 2024 looks on pace to surpass 2019’s record number of visitors to Japan.

I veered from typical lodgings and stayed in Ginza - a tactical error that won’t be repeated, but one that allowed me to confirm, at various hours, the depth and breadth of inbound tourism.

Most striking - my shuttle between domestic and international terminals at Haneda was all…fellow Americans, whereas I’m more accustomed to seeing travelers from elsewhere in Asia, particularly back in the 爆買い (explosive buying!) days of binge-buying Made in Japan goods.

Traveling in Japan in late May was also a reminder that Japan has a rainy season. The proximity of a typhoon meant we had horizontal rain the evening of May 28, the same evening as my talk on semiconductor clusters. The rain depressed turnout a bit - no casual fans here, just die-hards - but made for a fun scamper through the rain post-talk.

This did elicit a sense of deja vu - last time I gave a talk on clusters in Tokyo (on industrial clusters, in August 2022), we also had a delicious cloudburst that took the edge off the summer heat. (That same post is what led to connecting to the team at MIT AgeLab, which led to contributing a chapter to their upcoming book on Longevity Hubs around the world. What will come from this post??)

Clusters: locations, ecosystems, and opportunity

Last newsletter I shared my wonder in Tokyo’s ongoing evolution. The pandemic clearly has not stopped the city’s development. While in Tokyo I was delighted to give an in-person talk on industry clusters, co-organized by the Japan Society of Northern California (

On to our talk! First, thanks to the Tokyo office of Japan Society of Northern California and TMIP (Tokyo Marunouchi Innovation Platform) for co-hosting.

As I wrote last time, my goal in the talk was to cover the following (succinctly, since I had about 40-45 minutes):

the historic role of semiconductors in seeding innovation clusters

the employment multiplier from semiconductor fabrication

the increased attention by government to economic security and where fabrication takes place

the economics likely required for new fabs (especially in “cold start” sites like Columbus, OH, and Chitose, Hokkaido) to be sustainable

A lot to cover in 45 minutes! 😅 (Materials were in English, as some materials were based on class materials; narration was in Japanese.)

Why this topic now? The governments in the US and Japan are both investing a lot in on-shoring of semiconductor fabrication, and in so doing, are having to choose where (which company, in what county and what state). So, in framing this activity, I segmented the geographic recipients of government support in the US and Japan into two categories:

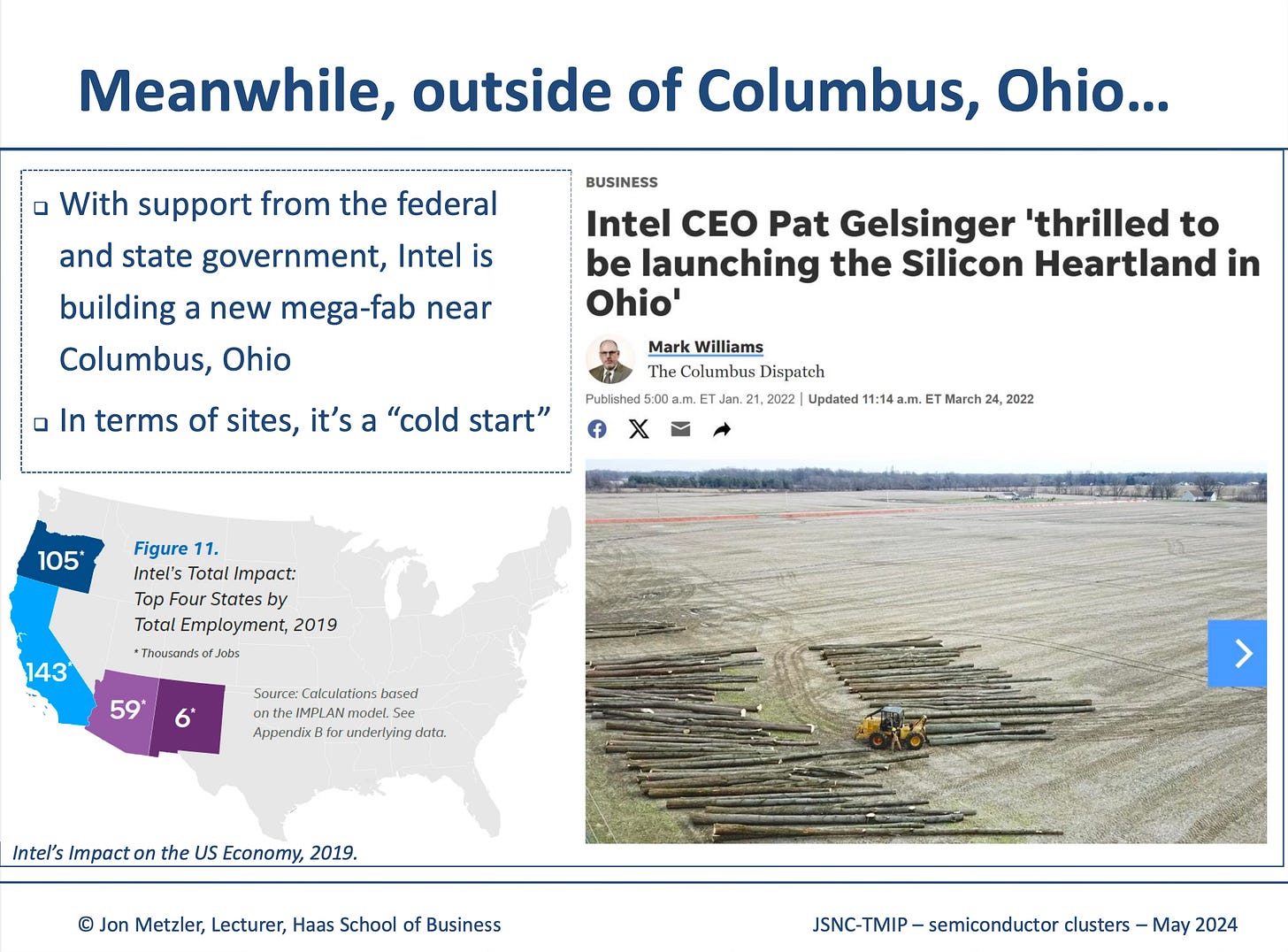

Cold starts: Chitose, Hokkaido (Rapidus fab site); Columbus, Ohio (Intel New Albany site)

Warm starts: Kumamoto, Kyushu (TSMC JASM site); Phoenix, AZ (Intel, TSMC sites)

Where “cold” or “warm” refers to whether those locations already were sites of semiconductor fabrication activity. Referring to our usual Cluster framework, in the warm start case, government subsidies should be amplifying what is already there. In the cold start case, government is trying to kick-start activity, and in doing so, can hopefully leverage factors that are already there.

For example, as of 2019, Intel was a major employer in four US states - California, Oregon, New Mexico and Arizona. Ohio, home of the in-progress New Albany fab (Columbus exurbs), was not one of the four.

But, there are other inputs already present in greater Columbus that government can hopefully leverage - universities, other manufacturing companies, infrastructure, and land. (Lots of land.)

In discussing the significance of where semiconductor fabrication takes places, I cited three factors. Some may be easier to model than others.

Long-term: the role of semiconductor fabrication in seeding innovation clusters, e.g. Silicon Valley; Austin; Boulder, CO; even Burlington, VT.

semiconductor manufacturing is a form of precision manufacturing, with a high employment multiplier

governments - and some businesses - today are more concerned with economic security and supply chain integrity

In this post, I’ll cover points 1 and 2.

On to point 1!

Long-term: the role of semiconductor fabrication in seeding innovation clusters, e.g. Silicon Valley; Austin; Boulder, CO; even Burlington, VT.

Here, I drew in particular on the Silicon Valley (Fairchild and Fairchildren) and Austin (Tracor, Technopolis Wheel) examples.

Particularly for cold start sites, this is probably the most aspirational of the three factors, and is offered with the benefit of hindsight, history, and some amount of what Porter’s Diamond Framework would call Chance (where Chance means Shockley choosing to move to Menlo Park, or Bill Gates and Paul Allen choosing to move back to Seattle from Albuquerque).

But, if you are, say, the state of Ohio offering subsidies to Intel, you are trying to induce a flywheel beyond the 3000 direct jobs (and other 15,000-20,000 indirect) the Intel New Albany fab will create. Within the US, the Silicon Forest outside of Portland is likely your best-outcome comparable, in terms of a US regional (i.e., not Boston or Silicon Valley) cluster. Intel alone is responsible for 4% of employment (direct and indirect) in the state of Oregon…50 years after first setting up in Aloha, Oregon. Another, perhaps more likely comparable is Arizona, where Intel is responsible for 1.5% of total employment, 40 years after its first fab in Arizona.

The Ohio Building and Construction Trades Council estimates 45M work-hours will be required on the first phase of New Albany alone. At $100/hour, that’s $4.5 billion in impact.

This all gets us to our second factor:

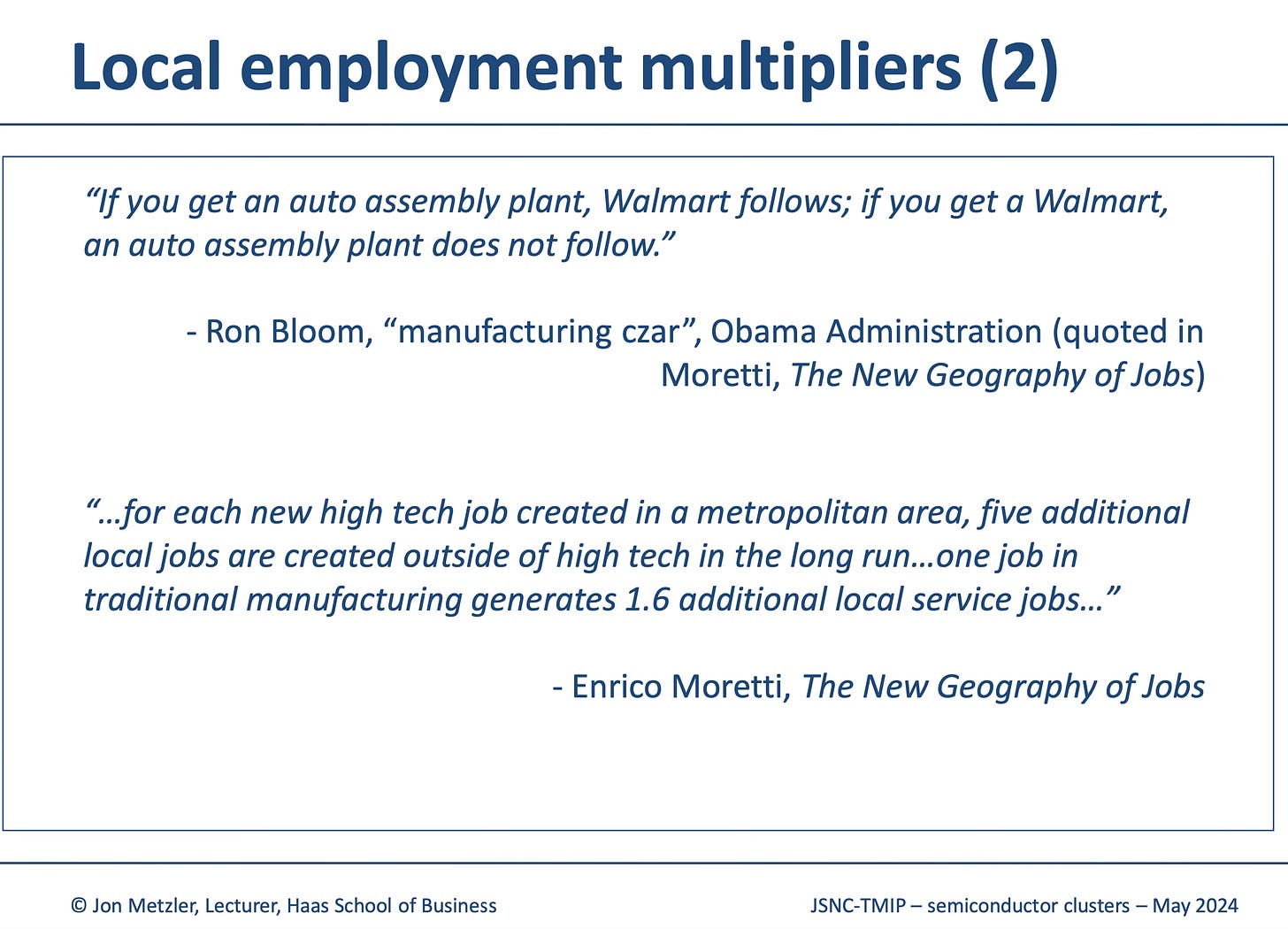

semiconductor manufacturing is a form of precision manufacturing, with a high employment multiplier

Here, a word of thanks to Matteo Tranchero, with whom I consulted with about recent articles in the literature about employment multipliers. Professor Tranchero (!) recently completed his doctorate at Haas and heads off to Wharton. Wharton’s gain is Haas’ loss - Matteo, we’ll leave the light on for you!

Ultimately, in looking at local employment effects, I referred to three works by UC-Berkeley’s own Enrico Moretti: a) a 2003 article on “million dollar plants”; b) a 2010 article on local multipliers; c) Moretti’s book, The New Geography of Jobs, which I use in Clusters class; plus, d) for a Japan-specific sample, research by Keio Professor Sachiko Kazekami on spillover effects on service sector jobs from office job or new business creation.

Moretti finds that 1 high tech job generally supports 5 other jobs, both skilled and unskilled, from construction workers to local baristas. Some high tech is more COGS-dense than others (say, semiconductor fabrication versus app developers for a social platform), but for the purposes of my talk, and given that it is corroborated by Intel’s own IMPLAN analysis of its employment impact, I adopted the 1:5 multiplier for last week’s talk, i.e., 5 skilled and unskilled jobs created for every direct job created.

Or, to paraphrase Ron Bloom, if you get a semiconductor fab, a Walmart can follow; if you get a Walmart, a semiconductor fab doesn’t necessarily follow.

During my trip to Japan, I heard a number of anecdotal comments that the opening of TSMC’s JASM plant in Kumamoto was causing local workers to quit their jobs to go to higher-paying jobs at TSMC. These were at the level of anecdote, of course, and didn’t provide, say, context on what job people were leaving and what that job paid.

(On the mere 20 months it took Kajima to build and open the JASM plant - as opposed to a rule of thumb of three years from start to shipping,

had an excellent post comparing TSMC’s speed in Kumamoto versus that in Phoenix.Workers leaving less well-paying jobs to go a higher-paying jobs at a new factory? That is, of course, what is supposed to happen, and is the point of enticing the million dollar billion dollar factory. Whether local businesses will then react by - recruiting more workers, and/or raising wages (as did a local bank in this article; wait, people would leave a bank to work at a fab??) - and whether other workers will then move to Kumamoto to enjoy the higher-paying jobs and live in appreciating (by Japan standards) housing is really the question. TSMC plans to hire another 1200 people for its next fab in Kumamoto, which by itself is 0.14% of the local labor population over age 15 (1200 out of ~850K).

Prof Kazekami finds the local multiplier in Japan, well, depends - on whether labor is mobile, and the type of job. She finds that workers with higher incomes (with marquee jobs, i.e., such as those in high tech) tend to spend more on education, and/or spend more out of prefecture, i.e., on online shopping. Construction is, of course, generally additive locally.

This was also a question that came up in discussion on Chitose, in Hokkaido. It was nice to reconnect with hospitality exec Cynthia Usui, who kindly came to the talk and asked, in essence, forget the fab - where will the local hospitality and service staff come from?

The data here is interesting. In the year between 2021-2022, only about 1.4% of residents of Japan moved from one prefecture to another (178K out of 125M total population). This compares to about 2.4% in the US. (The US data is a subset of total moves, and only refers to people who move to a different state. In total, 12.8% of Americans moved in 2021, but 6.7% of those stayed in the same county, and 3.3% moved to a different county in the same state).

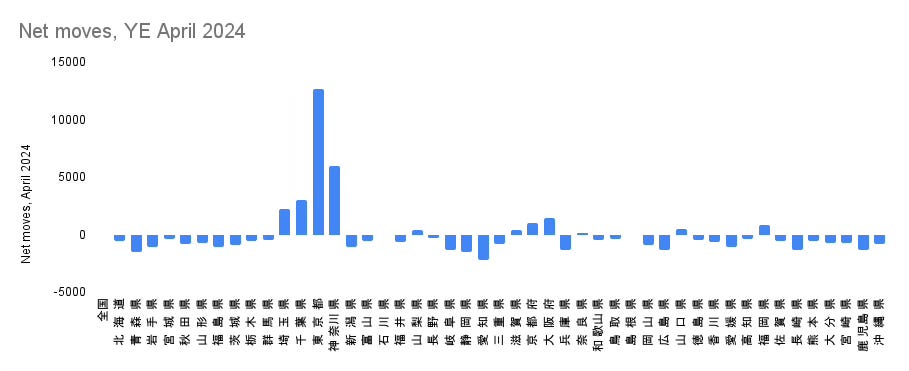

But, in the year ending in April 2024, about 3.2% of Japanese moved prefectures (and, not surprisingly Tokyo and Kanagawa were the big net “winners” - see table below - Tokyo is the big spike). Another 2.6% moved within the same prefecture. Kumamoto Prefecture, home of the new JASM factory, showed a net decline - more people moved out than moved in.

Btw, about 10% of those who move in Japan are non-Japanese residents, which over-indexes relative to the non-Japanese share of population (about 3%). This seems both intuitive and also worth watching.

Other nuggets from Q&A: questions rightly got into the issue of demand.

For example, would having more on-shore capacity in Japan lead to more on-shore demand, and device maker activity? This is indeed the $30 billion dollar question! Which is, wholly, a back-of-the-envelope number but one I will put forward for discussion purposes as 2X the cost of developing the Rapidus fab, or an annual level that ensures sufficient cash flow to build the next fab.

Post-talk interviews did indicate that while Rapidus is both getting the most funding and attention and faces the most ambiguity about demand, government support for other projects (e.g. JASM in Kumamoto, the rumored HBM capacity in Hiroshima) will likely be viewed as successful, as these projects were developed with demand already established.

Point 3: governments - and some businesses - today are more concerned with economic security and supply chain integrity

Point 3 refers to our current era of trying to induce re-shoring of semiconductor supply. And it takes us to the somewhat eye-of-the-beholder-dependent topic of economic security. Which as a term, merits definition. If it means, for example, resilience to certain supply shocks, i.e., not being subject to supplier holdup, say, during an earthquake, how much is that worth? Or can we think of this as more akin to second-sourcing, which is common practice in a lot of industries, including semiconductors, but by definition adds some amount of cost?

There’s Moore’s second Law, or Rock’s Law, which posits that the cost of a fab doubles every four years with advances in Moore’s (first) Law. Meaning, whatever the grounds are for establishing the fab, to fund the cost of the next generation of fab, it still needs to generate about 2X the cost of the fab in revenue, in order to stay at the technology frontier. In this portion of my talk, I borrowed from

‘s analysis of this - thanks, Jay!There’s enough to this that I will carve this element out as a separate post. Stay tuned.

Shifting gears, an early morning Tokyo jog took me past some interesting street furniture and for a moment I channeled my inner

- it was fun to see a legacy public payphone turned into public WiFi for the abovementioned tourists. (Of course, converting to WiFi probably meant upgrading backhaul too.). I spent a lot of time on payphones like these in the 1990s, both before and after getting my first pager. (To my surprise, I did see a payphone in use once this trip.)Come surf with me

On a Japan-themed note, Berkeley Haas is taking the show on the road - and will put on an alumni event in Tokyo on June 12th, hosted by Berkeley Haas board members Haruki Satomi and Seiichiro Yamamoto. Dean Ann Harrison will attend, as will Saikat Chaudhuri, faculty director of the M.E.T. program. (Alas, I cannot fly back to Tokyo to join. 😞 )

Last but not least, before I wrap up - a little throwback J-Pop, in honor of summer. Dreams Come True’s Haretara Ii Ne (It’s nice when it’s sunny), which, having been featured on the NHK series Hirari, was on heavy rotation during my first stay in Japan many moons ago.

Onward and upward,

Jon

while I'm still only on Part 1, my board colleague Satoru Watanabe came out with a full (Japanese-language) summary (if brief) of the talk. https://maximize.co.jp/news/240614/.