Friends - it was very nice to hear from many of you after my last post. Apparently I’m not alone in marveling over the Moss Landing stacks! Particularly when juxtaposed with kayakers, otters, and the surrounding Elkhorn Slough Reserve. To wit:

Elkhorn Slough Reserve, circa July 2021. Duck curve mitigation facility in the distance

**

A warm welcome to new subscribers - thanks for joining! By way of introduction, in this newsletter I generally cover themes related to my instruction:

Strategy for the Networked Economy

Clusters: Locations, Ecosystems and Opportunity

Business in Japan

Competitive Strategy

With the occasional foray off topic thrown in. Thanks for being here! I look forward to your feedback.

***

On to our post.

One of my most memorable site visits - ever - was to a Honda assembly plant in Japan in 2016. This was through the gracious introduction of Nick Sugimoto, a fellow Haas alum, and then CEO of Honda Innovations. I took a group of Haas MBA students. We got to see the welding and painting stages of a car being assembled. It was awesome.

The plant utilized industrial robots operating inside enclosures. There was clear demarcation between where humans could go, and where they could not. Watching parts and robots move in three-dimensional space and time, I first thought of the Seekers in The Matrix, but with roles reversed - here, assembly line workers were feeding the machines, as they helped slot new parts into the assembly line for the robots to then manipulate.

In gaming, and in sci-fi, there is the trope of the Maker, or the Architect - the builder of the game. (Plutarch in Hunger Games is an example.) Visiting the Honda plant made me want to meet the Architect who had modeled how the machines would move in time and space. The tableau I had witnessed lingered for days. I was grateful to Honda for hosting us. Our group - and hosts - are pictured below.

2016 Seminar in International Business: Japan - Honda plant visit

My Haas faculty colleague Roy Bahat (perhaps better known as head of Bloomberg Beta) uses the analogy of looms, slide rules and cranes in describing how we can apply AI in the workplace. I’ll try to apply that motif here. The industrial robots certainly lifted things humans could not (cranes) and with precision difficult for a human to replicate (slide rule) and produced cars more quickly and higher volume than humans could on their own (looms). But ultimately, they were very complementary, with the role of the robot and the line worker clearly defined and demarcated. They didn’t replace humans; they greatly augmented them.

Of course, we were witnessing the fruit of years of practice, to the point that Honda was willing to showcase it to an audience.

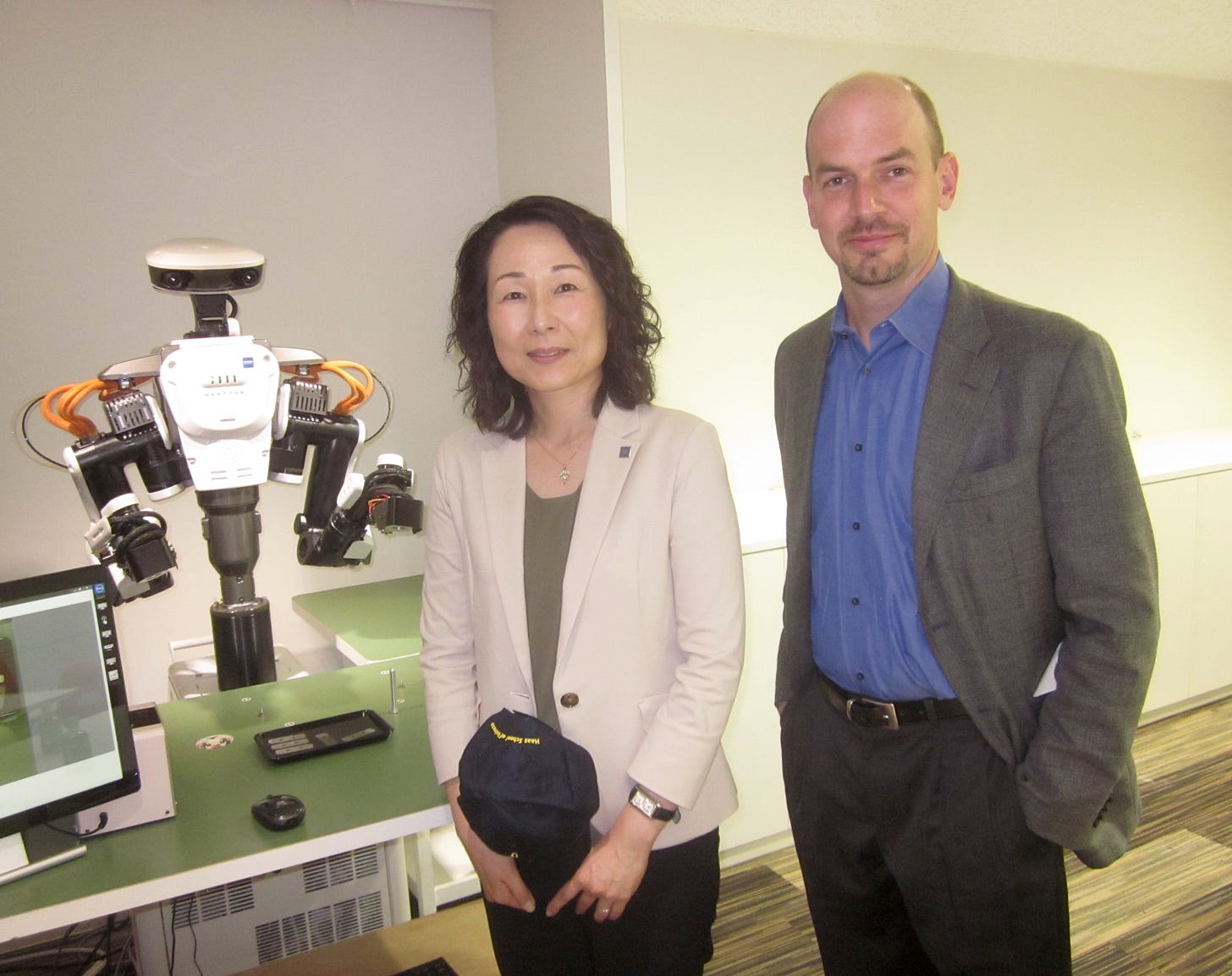

That same trip, we visited Kawada Robotics, which was working on cobots, or collaborative robots that could work side-by-side with humans, no enclosure required. This is a very different engineering problem. We saw a demonstration of their Nextage Robot. The cobots were anthropomorphic. They were gentler, slower, and clearly less risky to stand next to than the above industrial robots. My students broke into applause after one particular demonstration - they clearly wanted this somewhat cute robot to succeed! Perhaps there’s something to making the robot…endearing.

Kawada Robotics Nextage robot, circa 2016, and our host Noriko Kageki

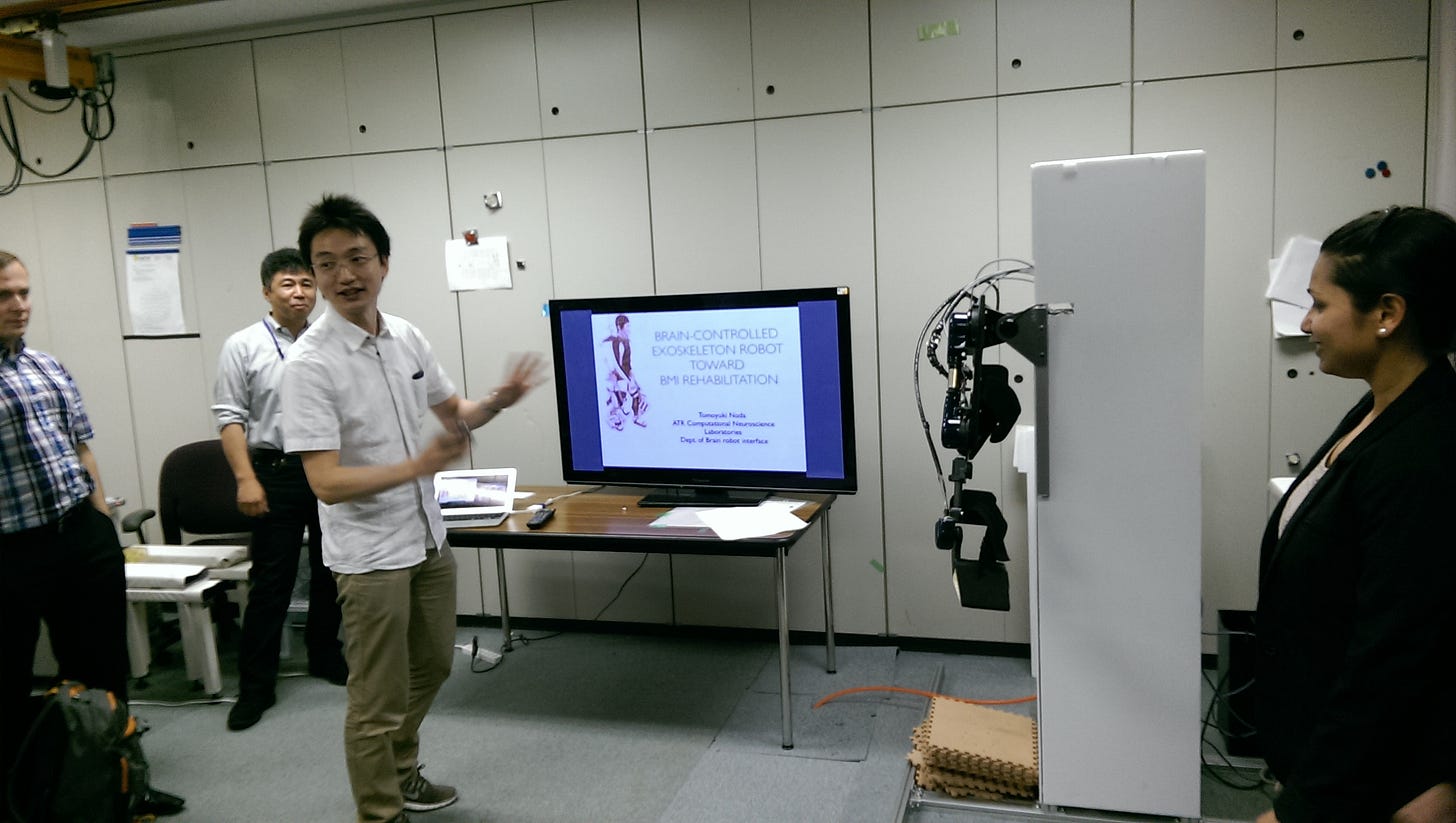

The previous year, I had taken that class to a research facility, ATR in Kyoto. We saw a demonstration of a robotic arm, designed to be able to help carry a 10 kg weight - not by coincidence, the weight of a heavy bag of rice.

And yes, we also visited the Ishiguro Lab.

***

These various initiatives aiming to augment human capabilities were on my mind during a lunchtime discussion with James Wright, researcher and author of the recent Robots Won’t Save Japan. The event was organized by the Japan Society of Northern California. The book is based on James’ research for his doctorate, during which he conducted ethnographic research on the development and deployment of caregiving robots in senior facilities in Japan. James graciously joined a lunchtime event for those of us on the West Coast; it was nighttime for him in Europe. Many thanks to James for joining and fielding some thorny questions live with our audience.

Robots depicted in the book and in James’ presentation include Pepper, Paro, and Hug. I took Hug - or Hug took me - for a test-ride recently. A staff member can tow hug once the patient - the hugged - leans into the device and is on board.

Ready for conveyance

Discussion with James was a Zoom event, given distance and time differences - here’s the view from home. The presentation James is sharing shows robot care device use cases envisaged by METI. I’ve linked to an English translation from AIST here.

One of the takeaways from James’ book and discussion was that the caregiving staff sometimes looked at the robots not necessarily as assistive, but rather as getting in the way of developing a relationship with the care recipient, i.e., the facility resident. Thus, they were not cranes, nor looms, nor even slide rules. Though, I might argue that a member of staff with a sore back - a common reported issue - might welcome the help a device like Hug could provide.

A word on semantics - a device like Fuji Innovation Lab’s Hug is best thought of a powered assistive device with a human operator wielding a controller. Robot, semantically, feels like a stretch. In the US, accordingly, Fuji is calling it an assistive device. Japan’s METI also refers to systems not that different from baby monitoring systems as robots. By this definition, a rollator (pictured below in the street in Kamakura in March 2023) is not a robot, since it doesn’t have an actuator, but devices like Hug feel more akin to powered rollators than they do, say, cobots. Thus, I suspect this journey is just the beginning, and iteration will bring improvement in resident and staff experience.

***

I recently had opportunity to hear Yong Lee, Assistant Professor of Technology, Economy, and Global Affairs with Notre Dame University, speak on the employment impact of caregiving robots in nursing homes in Japan. Prof Lee and his co-authors found that robots increased employment by necessitating temporary staff to help tend to the robots. In sum, the robots needed caregivers. This finding is consistent with James Wright’s ethnographic observations. Prof Lee’s sample in the 2021 version of his paper uses 2017 survey data from 860 nursing homes. Another finding was that homes adopting robots tended to have already adopted other assistive devices, such as adjustable beds and lifts for movement, and also had staffing managers worried about staff retention issues. Thus, more sophisticated homes tended to be earlier adopters.

**

Onward and upward,

Jon

Professor Metzler - hope this isn't a shot in the dark and that you remember me — you very kindly let me take 190 in my sophomore year (when it was called Strategy in the IT Firm) and hopefully enjoyed watching me struggle above my weight in a class that I was very underqualified for. So cool to stumble upon what reads like your similarly very kind, thoughtfully created newsletter, and hope the medium of a comment on it (+ subscription; of course!) does not dilute an out-of-the-blue hello and a very warranted thank you for shaping fundamentally the journey I've lead today. Excited to read more :-)

Useful insights, thanks for sharing. I’m sure in the end a large part of acceptance is going to be less about whether staff and residents like them, and more about whether they save money, staff time and have enabling regulations. Many clinical staff complain that EHRs are a pain and take them away from patient interaction, yet economics and government fiat rule.