Friends,

It was very nice to hear from some of you after my last post. Here in the Bay Area, we’ve been enjoying some much-needed rain, and even the rare bit of snow on Mt Tam and Mt Diablo. And up in the Sierras, LOTS of snow.

Which represents progress in the right direction from a drought perspective (WaPo gift link).

The spring semester is flying by. Spring B starts next week. I will meet half of FTMBA Class of 2024, in two cohorts of Strategy.

In Strategy for the Networked Economy, we are now entering the eighth week. One theme across classes is the business of managing subscription businesses. To that end, new for this year I have adopted The Business of Platforms, from Cusumano, Gower and Yoffie. (Here, two shout-outs: to my former Waseda host and collaborator Tatsuyuki Negoro, who hosted Cusumano in Japan in 2019 while we were jointly teaching Strategy for the ICT Firm; and my Haas faculty colleague Greg La Blanc, who hosted Yoffie on his Unsiloed Podcast back in February 2022.)

A second theme is that of innovation cycles in the networked economy.

That last bullet is a recurring theme - the progressively steeper barriers that arise when a company falls behind the innovation curve. This can lead to interesting examples of coopetition - Netflix, for example, choosing to migrate its origin servers over to Amazon Web Services, because it became progressively more diseconomic to run them themselves. (Netflix simultaneously operates its own CDN to ensure a good subscriber experience in the last-mile.) Netflix raised its own capital barriers on a different dimension by spending for talent, so clearly it had made a decision on where to invest, and where it could outsource.

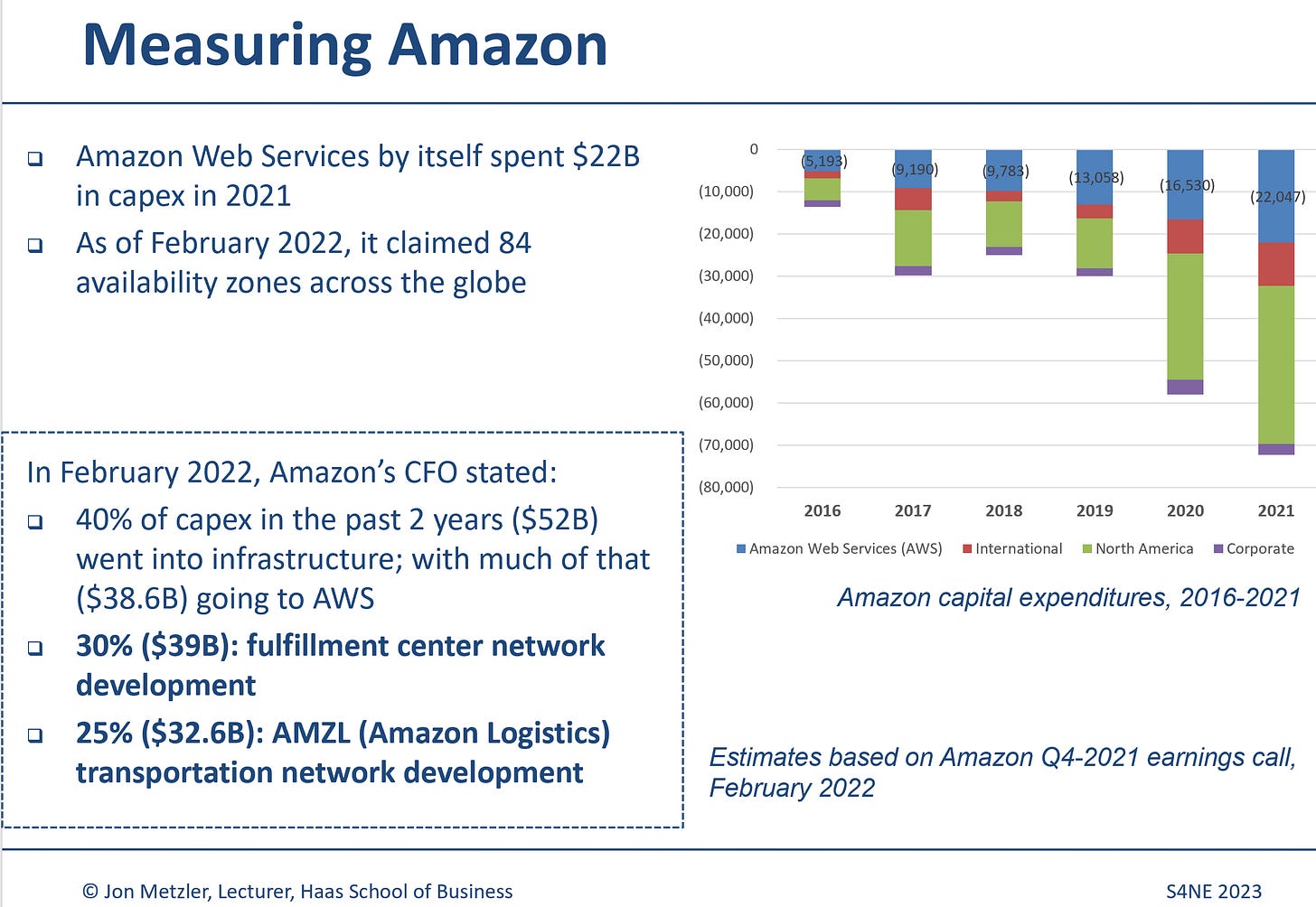

Amazon’s spending on capex is another example.

By comparison, here’s Fedex’s.

Not even Fedex comes close to Amazon’s investment flywheel.

The point being - a retailer (such as Gap, like we discussed in class) may choose not to distribute as a merchant on Amazon, but it should do cognizant of the tradeoffs and what reconstituting Amazon’s fulfillment capabilities sans Amazon itself would entail and cost. The capital barriers are that high.

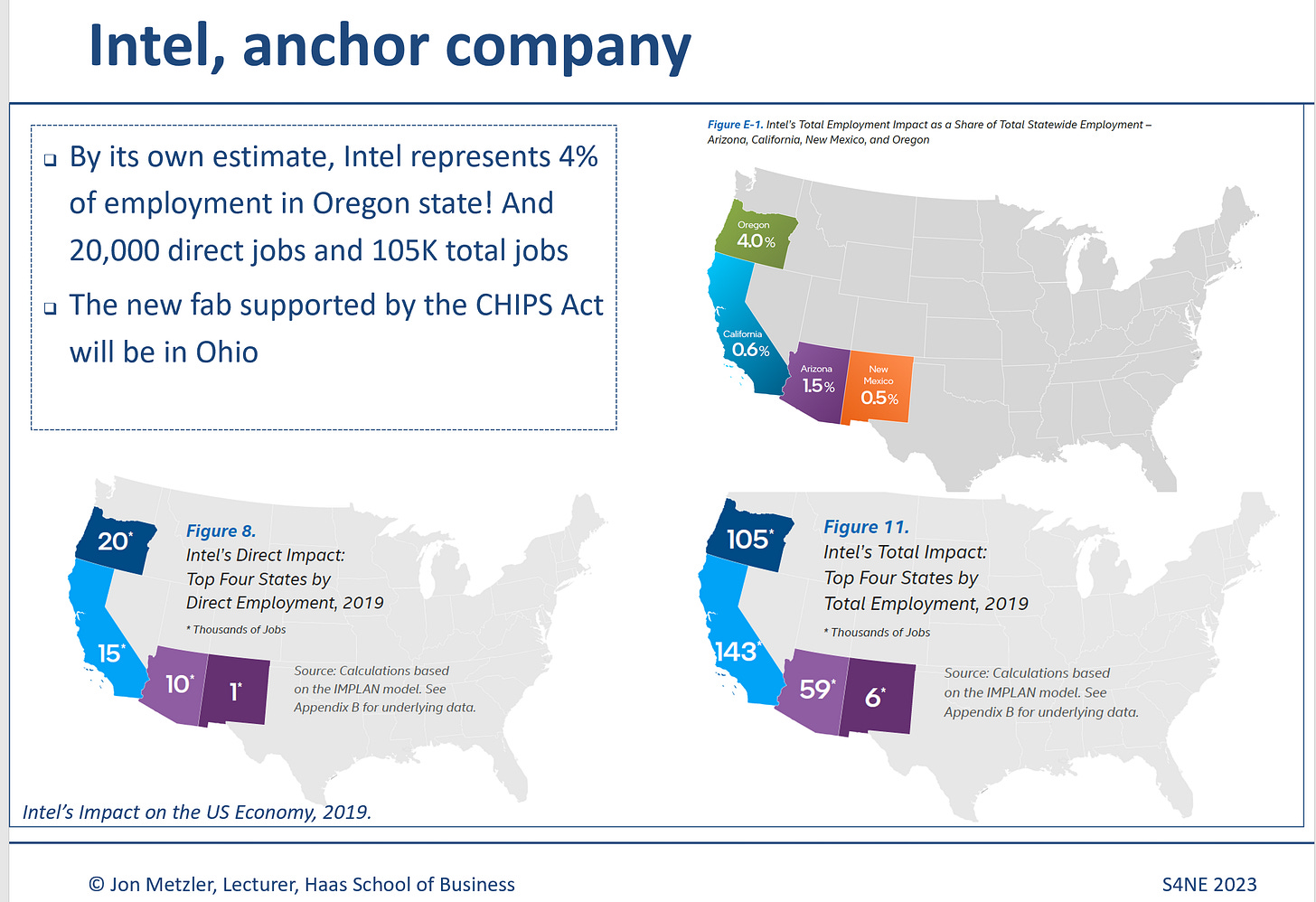

The topic of rising capital barriers brings us to Intel, largest of the Fairchildren, and anchor employer in California, Oregon, Arizona, New Mexico, and (hopefully) soon Ohio.

In Class 6, we discussed Intel, and its decision to outsource manufacture of leading semiconductor nodes to TSMC. This is, of course, a decision it backed into after years of development delays, first in getting to 10 nm, and then in progressing beyond that. Our case from Ivey provided the following chart, sourced originally from AnandTech.

Meanwhile, a look at TSMC’s 2022q4 earnings, which break out revenue by node generation, and the wedges move from quarter to quarter with regularity. (In TSMC’s case, each new node generation means a new fab, so one can also model the revenue contribution of each new building, which represents about $15B in capex.)

As has been well-covered, Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger returned from VMware and rather than spinning off Intel’s foundries, chose the hardest of hard paths: accelerating through 4 semiconductor node generations in 5 years, *and* creating a foundry business. Rephrased, go faster than Intel ever did, and, as one of the remaining IDMs (NVIDIA and AMD among others, are fabless), simultaneously develop a foundry business supporting external customers. Both are incredibly hard to do. Global Foundries, the former foundry business for AMD, took years to reach its current, trailing footing, with the benefit of patient shareholders.

Here I’ll share Dylan Patel’s read on Intel’s shareholder day in 2022, which covers a lot of what Gelsinger proposed.

(Dylan’s reaction in January 2023 to Intel trying to do this while preserving the dividend was rather less kind.)

To help unpack all this, I turned to an old friend and regular confidant - Jay Goldberg, author of the Digits to Dollars blog; founding team member at Snowcloud Capital; and alum of Murata, Qualcomm, DeutscheBank, among other accreditations. On February 7, Jay had published the following:

After their last set of results, especially their guidance for 2023, we are increasingly of the opinion that Intel is out of options. They forecast they are going to burn $15 billion in cash next year, a huge amount even for a company with $34 billion of net cash on their balance sheet. After their disastrous roadmap event last month, we have to call in to question the company’s ability to accurately forecast their business. We actually have many more examples of systematic flaws in their forecasting abilities, but none as public as that event. So we have little confidence in the company’s $15 billion forecast, it could easily be much higher. Add to that the need to continue to fund their manufacturing needs and their cash needs are immense.

and

This likely means that the only viable alternative is the one they are currently attempting – raise as much money as possible, beg the government for more, ignore the Street and run like Hell to Intel 20A.

On that note, here’s TSMC’s capex from the past six years (via Capital IQ. ballpark 28 NTD to USD, so about $38B in 2022). In January 2023, it announced modest *cuts* in capex, to $32-36B, in 2023. (Somewhere, Morris Chang is scowling at that decision.)

Across my MBA and undergrad classes, Jay, himself a Cal grad, has been a staple guest speaker and it was a delight to host him again.

Jay’s podcast on semiconductors with analyst Ben Bajarin (The Circuit, naturally) can be found on Spotify and elsewhere.

One thing I shared with my students in a subsequent class: as a student wrapping up their MBA and maybe entering a services role at one of the strategy firms, I have to say working on Intel’s attempted *leaps forward* would be an incredible opportunity.

Onward and upward -

Jon