Open RAN (2): mobile network operators and their suppliers

Also, operator capex and just how many base stations are there in the US?

(updated with RAN market concentration data post-publication)

Friends - this post continues a sequence of posts on the topic of Open RAN, or Open Radio Access Networks, or a move to (a) unbundle the RAN and (b) facilitate greater hardware and software interoperability between RAN suppliers.

I’ll continue these posts up to and following publication of an upcoming report on the topic, to be published by the UC-Berkeley Center for Long-Term Cybersecurity.

Missed my last post on the topic? Not to worry, here it is.

Let’s go way back - to American Bell Telephone, the antecedent to American Telephone & Telegraph Co (AT&T), which acquired its supplier Western Electric in 1882. This made Western Electric the sole supplier of Bell telephones and telephone equipment. This continued for decades, until the Carterfone decision of 1968, which enabled third-parties to develop equipment to attach to AT&T’s network.,

, The Carterfone, via ArsTechnica

In the modern era, mobile network operators, including those derived from the former Bell System (AT&T and Verizon) are generally integrators of products and services provided by established outside suppliers. Key suppliers include handset partners like Apple and Samsung, and network equipment partners, such as Ericsson, Nokia, and Huawei. While there is local market variance, especially with regards to handsets, major handset and network suppliers are used worldwide. In particular, a largely consistent set of network equipment suppliers is used across the globe. (In classes, I often refer to telecom as a global industry with pronounced local deltas, whether handsets or services.)

This has benefits to network operators: for example, operators currently deploying 5G networks can leverage the expertise that suppliers have accumulated over the course of rolling out networks elsewhere in the world. For example, Ericsson, headquartered in Stockholm, Sweden, claims to have customers in more than 180 countries. Meanwhile, the company’s network operator customers focus on customer acquisition and retention, network operation, and development and delivery of new services. Network operators are also responsible for acquisition of the wireless spectrum used to provide service, typically on an auction or an awarded basis.

The relationship between network operators and network equipment suppliers is one of co-specialization. Value is jointly created, and one does not exist without the other. Similar examples are seen in other mature industries, such as the automotive industry or the passenger air travel industry. While this co-specialization has enabled consistent service and sharing of best practices around the globe, the consolidation of the network equipment market, and the RAN (radio access network equipment) market in particular, means that network operators worldwide are dependent on the ability of a few key suppliers to continue to innovate.

[update post-publication/]

The RAN market is highly concentrated. Dell’Oro estimates that the top five RAN suppliers (Huawei, Ericsson, Nokia, ZTE, Samsung) captured 95.2% of revenue share in 2022, slightly down from 2021 (95.8%); Omdia estimates the top five suppliers captured 94.6% of revenue in 2022. Dell’Oro estimates that the market grew slightly more concentrated in 2023.

The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) is a measure of industry concentration. Using Dell’Oro estimates of top five RAN supplier revenue share, we calculate HHI for the RAN supplier market for the years 2021 and 2022 as 2269 and 2229, respectively. The overall HHI score declined slightly year-over-year, due to a slight redistribution of share between the top five RAN suppliers. Still, the RAN market remains concentrated overall. The US Department of Justice, in guidelines updated in January 2024, considers markets with HHI scores in excess of 1800 to be highly concentrated.

How does the HHI work? The score is the sum of the squares of the market shares of individual providers to that market.

A market with one seller would have a score of 10,000 (100^2).

A market with two sellers (say, passenger air travel) would have a score of 5000 (50^2 + 50^2)

A market with three sellers (note that the Big 3 RAN players of Huawei, Ericsson and Nokia have >75% combined revenue share) would have a score of 3267 (33^2 x 3)

[/update]

There are many well-known examples of co-specialization, particularly in technology markets. Recent examples include Apple and Foxconn, Apple’s main manufacturing partner; NVIDIA and TSMC, NVIDIA’s main fabrication partner; or Tesla and its battery suppliers, such as Panasonic and LG Chemical.

Speaking of co-specialization, here’s a fun digression: time lapse of development of the Reno GigaFactory (circa 2016), co-developed by Tesla and battery partner Panasonic.

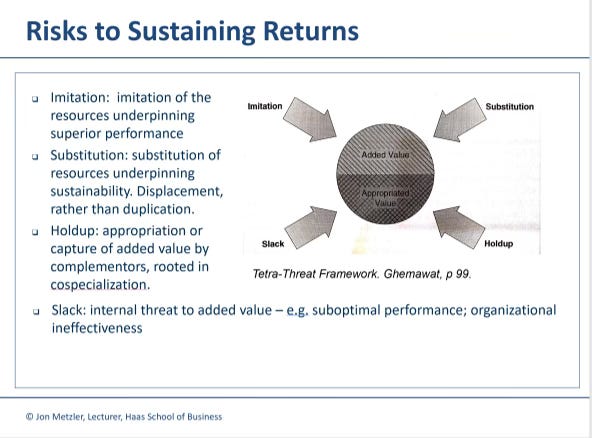

Strategist Pankaj Ghemawat, in his classic article Sustaining Superior Performance (with Gary Pisano), highlights four forms of risk to sustaining corporate performance: imitation, substitution, holdup, and slack.

Imitation refers to competition by alternate providers using largely the same assets and capabilities (e.g., lower-cost alternatives);

substitution refers to some alternate form of fulfilling the same customer need (e.g., substitution from netbooks to tablets, or from PC to mobile);

slack refers to underperformance relative to the company’s capabilities, due perhaps to bureaucracy or coordination costs (i.e., diseconomies of scope or scale); and

holdup refers to value appropriated by co-specialization partners.

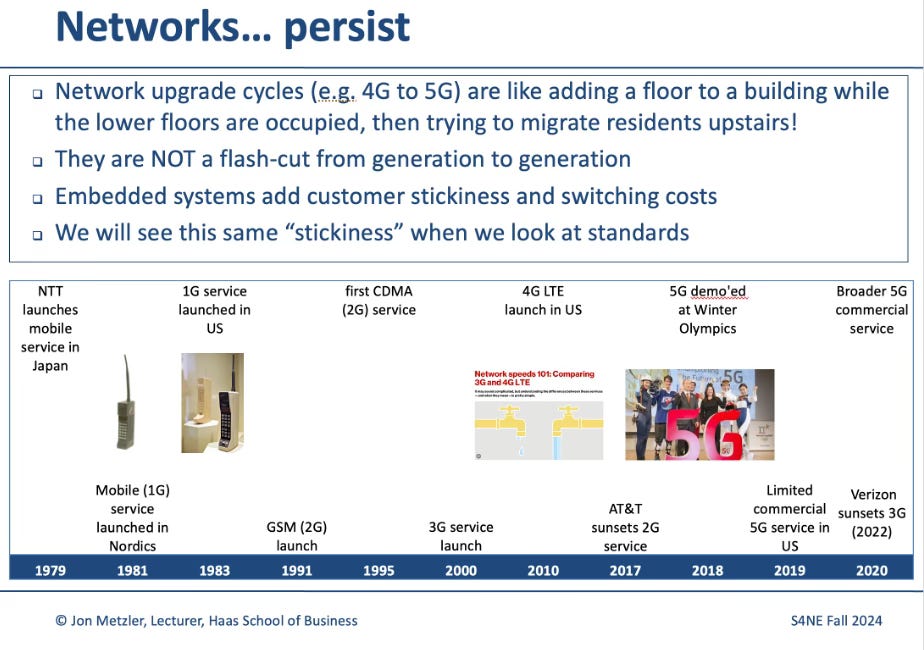

Lock-in between cellular network operators and their network supplier partners is high. Operators do switch suppliers, sometimes in the process of transitioning to new generations. Huawei, for example, greatly expanded its share globally during the migration to 4G. But generally, incumbency in one generation (say, 4G) is advantageous when operators are assessing the next generation, particularly since network operators typically have multiple generations of network technology running in parallel. But, given the relationship of co-specialization, and given how the same five major RAN suppliers are used worldwide - something were to happen to a key supplier - a disruption, or, inability to keep innovating - the broader industry would suffer.

A more local way to think about this - all three major US carriers rely on Ericsson, and by extension, so too does the US connected economy.

The RAN market, telecom equipment market, and network operator capital expenditures

Radio access network (RAN) equipment refers to equipment in a wireless telecommunications system that provides the wireless access link with the customer handset (e.g., smartphones, sometimes known as user equipment or UE), and also manages radio resources. Product examples include antennas, remote radio heads, baseband units, fronthaul and backhaul transport products, and related software and silicon products. These are shown in a 5G configuration in the diagram from Nokia Networks below.

5G RAN deployment configuration. Nokia Networks, 2020. RU: radio unit; DU: distributed unit; CU: control unit. These roughly correspond to BTS, BSC and MSC from the 2G era.

Traffic from the mobile wireless network is relayed back to a core wired network. Depending on the network operator, the RAN equipment provider may be involved in operation and support of its own equipment within the operator network.

While makers of RAN equipment conceivably have the capabilities to stand up wireless carriers themselves (and may indeed manage networks on behalf of their customers), they are largely B2B companies. Exceptions are the handset business units that some RAN suppliers retain, such as Samsung and Huawei. These engage in direct consumer marketing, if not service provision and billing. Network equipment suppliers that also have handset businesses may choose to bundle handsets with network equipment when contracting with network operators.

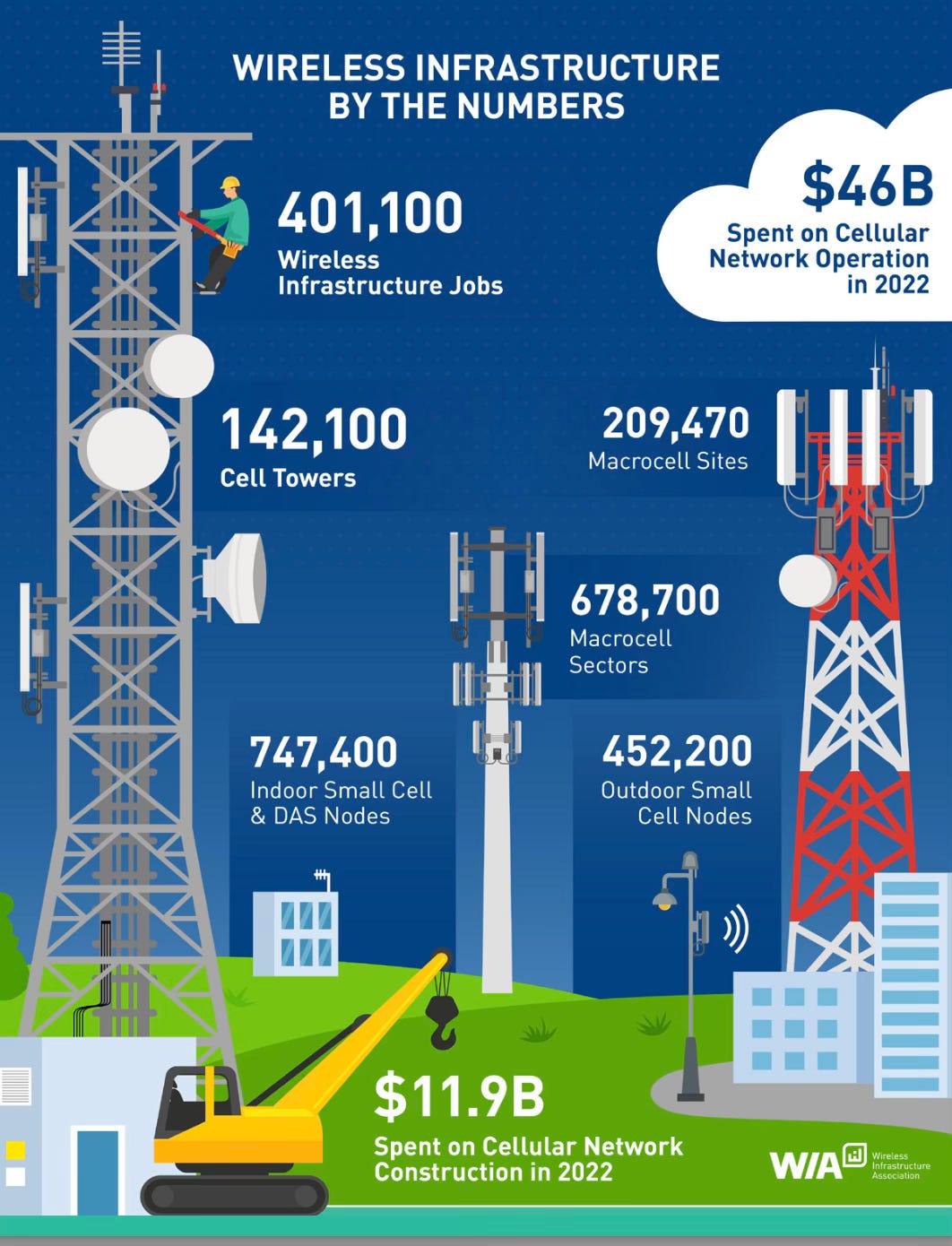

The Wireless Infrastructure Association (WIA) estimates that there are 142,000 cell towers and 209,470 macrocells in the United States. One tower, particularly any of those operated by specialist third-party tower operators like American Tower Corporation or Crown Castle Inc., may host equipment from multiple operators in a host-tenant model. The WIA further estimates there are an additional 747,400 indoor small cells and 452,000 outdoor small cells in the US. In its 2022 member survey, CTIA, the US wireless carrier association, estimated that there were 419,000 operational cell sites in the US.

Wireless Infrastructure Association, 2023

In comparison, data from China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) indicates that, as of February 2024, there were 3.5 million 5G base stations in China, and close to 12 million base stations in total in China when including all network technology generations.

RAN above your local movie theater; Mill Valley, CA

GSMA estimates that global network operators will spend $1.5 trillion in capital expenditures between 2023-2030, or close to $190 billion annually. In the United States, CTIA, in its 2023 member survey, estimated that network operators invested $39 billion in their networks in 2022, up from $35 billion in 2021. As a rule of thumb, roughly one-third of network operators’ capital expenditures go toward access equipment. Other expenditures include civil costs (construction), transport equipment, cloud infrastructure, IT, and software.

As of 2022, Dell’Oro estimated the global telecom equipment market at $100 billion, with the RAN segment at about $41B.

More to come on this topic!

Also coming up - a look back at the fall 2024 semester; a Chartbook-y style year in review; and also, the year in reading. As a (p)review, here’s last year’s year in reading.

2023: the year in reading

Friends - Happy holidays! This will be my last post of the year, so I’ll look back at readings that were particularly impactful over the course of the year.

Since we are now in the holiday season, I can, without shame, drop some holiday music. With that, here’s Bay Area local Adam Shulman playing from the Charlie Brown Christmas soundtrack in 2023 (a show my better half and I may have attended…)

Onward and upward,

Jon